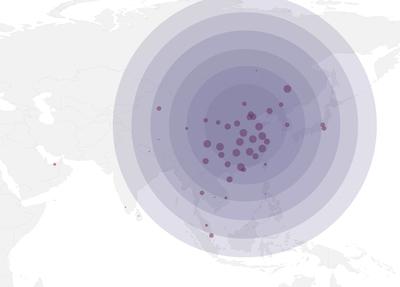

Mapped: The rapid spread of the new coronavirus in China and beyond

Tracking the global response to the coronavirus outbreak.

The number of countries reporting coronavirus infections continues to climb, as health authorities rush to contain what the World Health Organisation is now calling a pandemic.

Confirmed coronavirus cases have been reported in the Middle East, Africa, Europe, North and South America, the Caribbean, and Australia and New Zealand. (TNH)

"We are deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction," said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

Global confirmed cases of the coronavirus reached roughly 125,000 by 12 March, including more than 4,600 deaths. At least 110 countries or territories are now reporting infections. The outbreak's rapid spread – there were only 30 jurisdictions with confirmed cases as recently as 21 February – is fuelling fears that the virus has gained a global foothold and is a growing threat to countries with weak health systems and large refugee and migrant populations.

The Democratic Republic of Congo announced its first coronavirus case this week – just days after the country's last Ebola patient was discharged. A growing list of countries already facing humanitarian emergencies or instability – Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, Iraq, or Afghanistan, for example – are also reporting infections.

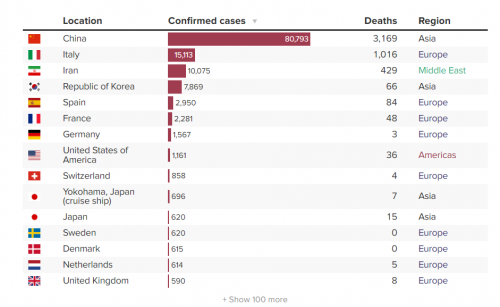

Most of the cumulative cases and deaths are in mainland China, but there are now far more new daily infections being reported outside China than in it.

The illness caused by the virus is officially known as Covid-19, short for "coronavirus disease 2019".

Confirmed coronavirus cases

Updated 12 March 2020

Source: National health authorities: Hong Kong Department of Health;WHO

More than 80 percent of China’s cases are found in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province and the outbreak's epicentre. Chinese authorities first publicly reported the emergence of a new respiratory illness with pneumonia-like symptoms in Wuhan on 31 December. The new coronavirus rapidly reached every province or region in mainland China before peaking in early February. Infections have been on a steady decline since then: China has reported only a few dozen new daily cases since 7 March.

Outside China, however, infections continue to multiply as the outbreak escalates in epicentres thousands of kilometres away. Since mid-February, dozens of countries or territories have reported new coronavirus infections linked to people travelling from Italy or Iran in particular.

Some Asian nations that saw a handful of the first imported cases in January are now reporting a second wave of infections. Confirmed cases have reached the Middle East, Africa, Europe, the Americas, the Caribbean, and Australia and New Zealand.

The Democratic Republic of Congo and Burkina Faso are among more than 10 African nations that have recorded confirmed cases. Testing is underway elsewhere on the continent.

The WHO has launched a $675 million response plan aimed at helping countries with weaker health systems get ready. It previously declared the virus outbreak a global health emergency – known as a public health emergency of international concern, or PHEIC.

While the coronavirus outbreak is spreading rapidly, it can still be suppressed and controlled, the WHO's Tedros said. The majority of the cases are in four countries, but two of them – China and South Korea – have "significantly declining epidemics", he said.

"All countries can still change the course of this pandemic," he said.

Why is there disagreement about global containment efforts?

There are unanswered questions about the virus itself and how to contain it.

The WHO says at least 72 countries have erected some form of travel restrictions. As the outbreak escalates, more countries are ratcheting up these restrictions, imposing mandatory quarantines, and suspending flights. But there’s disagreement among public health professionals about whether border shutdowns and screenings are effective – or even counterproductive.

The WHO says border closures and travel restrictions likely delayed the spread of the virus but did not prevent it. Public health experts say border closures can exacerbate outbreaks by driving migration underground – away from public health systems.

The WHO has been cautious about border restrictions and even screenings when taking the rare step of declaring global health emergencies.

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control says the effectiveness of coronavirus entry screening is “low” – its models estimated that three quarters of cases would go undetected.

Separate estimates by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine found thermal scanning might only flag one in every five arriving passengers infected with the virus.

Just as important are public education and robust medical follow-up procedures to ensure people who do develop symptoms know to seek out healthcare – and that healthcare staff know the signs and what to do. The Lancet medical journal has urged that frontline clinics – not just higher-level disease-control centres – are “armed” with diagnostic kits.

When the WHO declared a PHEIC for the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo last year, it warned against shutting borders or imposing travel restrictions.

“Such measures are usually implemented out of fear and have no basis in science,” the WHO said at the time. “They push the movement of people and goods to informal border crossings that are not monitored, thus increasing the chances of the spread of disease.”

Under international health regulations, countries are obligated to justify their emergency border restrictions with the WHO. At least 23 have done so, but it’s unclear what, if any, actions the agency will take.

Are there undetected cases?

The outbreak’s rapid evolution means that researchers have been rushing to study the virus in real time – and revising early estimates that become obsolete by the day.

Much of this research was focused on China, but attention is now pivoting as cases surge elsewhere. Iran has announced thousands of confirmed cases since mid-February, but critics have accused Iranian authorities of downplaying or concealing the extent of the outbreak.

One study published by Canadian researchers estimated there were actually 18,300 infections in Iran in February (when the country was reporting fewer than 50 patients), based on confirmed cases from Iran showing up in Canada, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates. The study, based on calculations including airline traffic data, also concluded that nearer countries like Syria are likely to have infections despite not reporting cases.

"The lack of identified Covid-19 cases in countries with far closer travel ties to Iran suggests that cases in these countries are likely being missed, rather than being truly absent," the researchers said. "This is concerning, both for public health in Iran itself, and because of the high likelihood for outward dissemination of the epidemic to neighbouring countries with lower capacity to respond to infectious diseases epidemics."

Health experts warn that all such studies are based on models that rely on incomplete data and assumptions – useful for estimating risk or potential spread, but far from definitive.

source: The New Humanitarian

- 342 reads

Human Rights

Fostering a More Humane World: The 28th Eurasian Economic Summi

Conscience, Hope, and Action: Keys to Global Peace and Sustainability

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020