Xi Jinping’s New Silk Road: Reviving Confucian Culture - Part 1

China has launched something for the world which has never existed before in human society. The creation of the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) in the Summer of 2014, and China’s inauguration of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in the Spring of 2015, with 48 nations signing on as Founding Members (despite intense pressure from the Obama Administration to boycott China’s initiative), marks the beginning of a revolutionary transformation of civilization. This historic process can only be understood in the context of the cultural and economic decay now driving the United States into both economic collapse and strategic confrontation with Russia and China, which could soon explode into global thermonuclear war and the annihilation of civilization as we know it, while China is undergoing a renaissance of the great Confucian culture which has driven every period of progress and scientific advance in the history of modern China.

President Xi Jinping’s announcement of the New Silk Road at the September 2013 meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Kazakhstan, and the New Maritime Silk Road in Indonesia in October 2014, touched off what has now become, together with the BRICS initiative, the greatest burst of infrastructure development on a global scale in history. The only comparable process was the vast infrastructure development of the United States by Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s—except this new process is global in scope. Xi Jinping has even called personally on President Obama to join the process, bringing the world together to raise the standard of living and productivity of the human race, in a “harmony of interests” which America once championed as its own. Today it is the concept of Harmony introduced by Confucius (551-479 BC) which is inspiring China to offer “win-win” cooperation among all nations in great infrastructure projects of benefit to all mankind.

The ugly reality of the current global crisis is that the United States, under the Bush and Obama Presidencies, is a decadent, dying culture, fostering deadly austerity, perpetual warfare, and licentious social degeneracy, which is openly attempting to destroy the cultural optimism of the Chinese nation, and its vision and dedication to global development.

Ironically, the current renaissance taking place in China is significantly influenced by the “Harmony of Interests” which characterized the original American System of political economy, which was introduced into China by perhaps its greatest citizen, Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925), the father of the Republican Revolution in 1911, overthrowing the imperial Qing Dynasty and bringing the American System of Alexander Hamilton to China. Sadly, that American System has been systematically destroyed in the America of the Bushes and Obama, even while it is alive and well in China.

These developments in China and the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) have been a victory for Lyndon and Helga LaRouche, who began an international campaign for the New Silk Road soon after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, as a means of bringing the nations of the world together around great development projects of mutual benefit.

In her recent series of meetings in China, Helga Zepp-LaRouche emphasized the importance of the dozens of conferences around the world, organized by the Schiller Institute (founded by Mrs. LaRouche in 1984), calling for the New Silk Road as a basis for ending the imperial Cold War divisions of the world once and for all, and unleashing the creative potential of the human race.

Sun Yat-sen and the American System

Sun Yat-sen was at the same time a Confucian, a Christian, and an advocate of the American System. Nearly a century ago, he set in motion the process which Xi Jinping has now embraced, while taking it far beyond Sun’s original design.

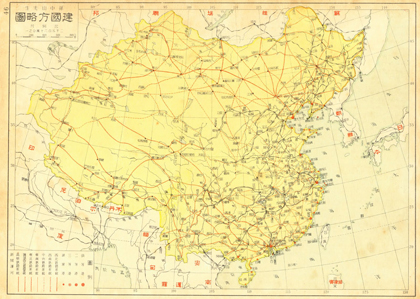

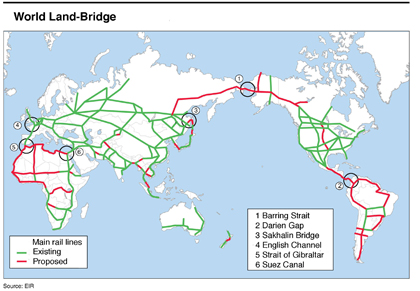

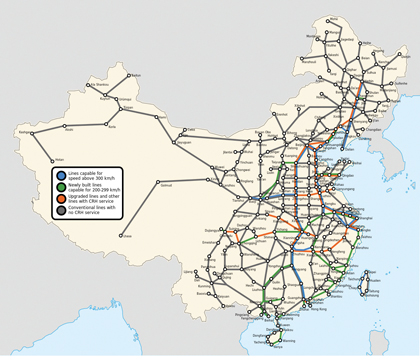

A comparison of three maps provides a graphic demonstration of the historical connections between the vision of Sun Yat-sen, the proposals of the LaRouches, and the policies and plans of President Xi Jinping today. These are:

Figure 1, Sun Yat-sen’s 1919 proposal for a vast railroad and canal development for China, reaching out into Russia, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia;

Figure 2, the three prongs of the New Silk Road (then called the Eurasian Land-Bridge) proposed in 1992 by Lyndon and Helga LaRouche—the northern route through Russia, the central route through Central Asia, and the southern route through Southeast Asia; and

Figure 3, showing China’s current rail network and proposed extensions. The philosophical connection among these three, while not as easy to demonstrate through sense perception, is the more profound, the more crucial to understand, if the world is to survive and prosper in this moment of crisis.

Sun’s proposal came at a moment of global crisis similar to our own. With the conclusion of the British-instigated world war (later called World War I), Sun foresaw the future. “The recent World War,” he wrote, “has proved to mankind that war is ruinous to both the conqueror and the conquered, and worse for the aggressor. What is true in military warfare is more so in trade warfare. I propose to end the trade war by cooperation and mutual help in the development of China. This will root out probably the greatest cause of future wars. The world has been greatly benefitted by the development of America as an industrial and commercial nation. So a developed China, with her 400 millions of population, will be another New World in the economic sense.” If the Western nations were to apply the war machine to such great developments, he warned, a new war would be inevitable—as indeed it was.

Sun was a student of the American System of Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln. Unfortunately, as he recognized clearly, under the Presidency of British imperial asset Woodrow Wilson after the war, “the U.S. has completely failed in peace, in spite of her great success in war. Thus, the world has been thrown back to her pre-war condition. The scrambling for territories, the struggle for food, and the fighting for raw materials will begin anew.” The West refused to heed his advice or to support his proposals—and, as he had warned, a new, more horrible depression and war ensued in the 1930s and 1940s.

We are now facing a far more horrendous crisis of civilization, as President Obama is following the British Empire’s drive for war on Russia and China, in an age of thermonuclear weaponry. Sun Yat-sen’s Confucian and American System advice has been heard by today’s Chinese leaders, as well as by Russia’s current leaders. Americans would do well to study his work, to help restore the American System in the U.S. itself.

Sun’s Confucianism

Sun was a converted Christian, having learned about Christianity from his American teachers in Hawaii, where he had gone from his home in southern China with his brother in the 1870s and ’80s to work and study.

But Sun was also a Confucian, although he was a fierce opponent of the ideology of the dominant Confucian leaders of his day, who had accommodated themselves to both the degenerate imperial rulers of the Qing Dynasty and the even more degenerate British imperial overlords of China at the end of the 19th Century.

When the British gunboats arrived in China, loaded with opium to enslave the Chinese people, they did what they always did in nations targeted for colonial domination—they profiled the philosophical currents there, in order to support those Aristotelian currents which rejected the Platonic view of man as a creative being, dedicated to uplifting all human beings through republican principles and scientific investigation. The Aristotelian tradition instead views man as an animal, born either master or slave, and willing to submit to the power of nature rather than to master it.

In China, they found this degenerate view within the Daoist and Legalist traditions, which had opposed Confucianism from its inception. In particular, they embraced a school which, although it called itself Confucian, rejected the Confucian view of man based on the creative powers of the mind, in favor of the philological study of the original Confucian texts, called Evidential Research, arguing that no changes could be made from the literal interpretation of those texts—i.e., pure British empiricism.

These scholars, who were also local government officials due to the Chinese system of choosing officials based on examinations of the Confucian texts, not surprisingly became the compradors of the British opium traders, centered in Canton (today’s Guangzhou).

Sun’s Confucian worldview drew instead on the tradition of the greatest mind of the Sung Dynasty’s Confucian Renaissance of the 12th Century, Zhu Xi. Zhu Xi and his School of Principle (Li) revived the teachings of Confucius and his follower Mencius, much as the European Renaissance revived the teachings of Plato from Greek antiquity.

This Confucian worldview was consistent with the European Renaissance view of man characterized by the great philosophers and statesmen Nicholas of Cusa and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and with the American System of Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton, which was itself inspired by the works of(1646-1716). Leibniz recognized his own concept of the monad in Zhu Xi’s concept of Li, meaning “principle.” To Zhu Xi, Li was a universal, eternal principle, indivisible, beyond time or place, and prior to all created things, governing the order of things and events. Each individual thing possessed its own principle, which found its meaning in its relationship to the universal. To Leibniz, this corresponded to his discovery of the monad, the concept that all created things are defined not in themselves, but through their connection to the universe as a whole, through the constant process of change and development.

Zhu Xi and the American System

Leibniz was, in a certain fundamental sense, the founder of the American System of Political Economy developed by such Leibnizians as Cotton Mather and Benjamin Franklin, and inherited much later by Sun Yat-sen as a student in Hawaii. The concept of the “pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence came from Leibniz’s idea of happiness as the singular fruit of virtue. The American System principle of physical economy, located in scientific discovery, also came directly from Leibniz. It is thus instructive to note the close relationship between the Preamble to the American Constitution and one of the most important contributions to Chinese philosophical thought by Zhu Xi.

To develop his notion of scientific method, Zhu Xi drew upon the most famous passage from the Book of Rites (one of the “Four Books”—the Confucian classics), the preface to the Great Learning, believed to have been written by Confucius himself. The passage is compared here to the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution:

The Great Learning, from the Book of Rites, as interpreted by Zhu Xi:

The ancients, wishing that all men under Heaven keep their inborn luminous virtue unobscured, first had to govern the nation well; wishing to govern the nation well, they first established harmony in their household; wishing to establish harmony within their households, they first cultivated themselves; wishing to cultivate themselves, they first set their minds in the right; wishing to set their minds in the right, they first developed sincerity of thought; wishing to have sincerity of thought, they first extended their knowledge to the utmost. The extension of knowledge to the utmost lies in fully apprehending the principle of things.

Preamble to the U.S. Constitution:

We, the people to the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America [emphasis added].

The Classical Chinese text, like all Classical writing, was poetic in nature, and thus metaphoric rather than rigidly precise (despite the foolish arguments of the British compradors in the Evidential Research sect). Zhu Xi interpreted the above passage in two ways that differed from traditional interpretations, and in so doing, enhanced the power of the underlying concepts, laying the basis for the 12th-Century Confucian Renaissance under the Song Dynasty.

First, the words in the opening passage: “The ancients, wishing that all men under Heaven keep their inborn luminous virtue unobscured,” had been previously interpreted as, “The ancients, in order to manifest luminous virtue to all under Heaven,” i.e., implying that the ruler alone must manifest virtue in order to achieve good government. Zhu Xi insisted that the passage conveyed a far broader meaning: that all men were born with luminous virtue, and that the purpose of government was to uplift the natural, virtuous qualities of all mankind, just as the U.S. Constitution holds that a more perfect union depends upon the promotion of the general welfare, and the Declaration of Independence affirms the “pursuit of happiness” through the development of one’s creative powers.

Zhu Xi’s second new interpretation came in the concluding passage. He argued that the notion of “extending knowledge” demanded more than the empirical investigation of things, if that were interpreted as merely recording sense impressions. Rather, Zhu Xi insisted that true knowledge lies only in fully apprehending the principle in things. Besides the many physical attributes of things and events, one must investigate the invisible qualities, those characteristics which connect the object (or event) in a causal way to the changing universe—what Leibniz called analysis situs. Zhu Xi wrote that this method, applied with diligence, would reveal “the manifest and the hidden, the subtle and the obvious qualities of all things.”

This pinpoints why Sun identified profoundly with Zhu Xi’s Song Dynasty renaissance of Confucianism, and simultaneously with the American System. It also shows why he rejected the Evidentiary Research school of the British compradors, who insisted that no change is possible.

The Book of Rites thus placed a rigorous scientific method as the foundation for each link of a causal chain: as the necessary source of knowledge, of sincerity of thought, of self-cultivation, of domestic harmony, and of good government.

It was this universal conception, as developed by Zhu Xi, which was the epistemological basis for both the artistic and the scientific developments of the Song Dynasty’s Confucian Renaissance, and the explosive economic and demographic growth during that period.

Leibniz was in direct contact with the Jesuit missionaries in China in the 17th and 18th centuries, who had taken the scientific works of Johannes Kepler and other Renaissance scientists and musicians to China, and had translated the works of Confucius, Mencius, and Zhu Xi. Leibniz, who published a journal titled Novissima Sinica (News from China) based on his correspondence with the Jesuit missionaries, described the potential scientific and cultural cooperation between Europe and China this way:

“I consider it a singular plan of the fates that human cultivation and refinement should today be concentrated, as it were, in the two extremes of our continent, in Europe and in China, which adorns the Orient as Europe does the opposite edge of the earth. Perhaps Supreme Providence has ordained such an arrangement, so that, as the most cultivated and distant peoples stretch out their arms to each other, those in between may gradually be brought to a better way of life.”

But this was not to be—at least not at that time. The Venetian imperial factions within the Church in Rome rejected the idea that the “heathen” Chinese could embrace Christianity without first rejecting the entire Confucian intellectual tradition of Chinese history. Since leadership in China was selected on the basis of one’s knowledge and practice of the Confucian moral teachings, as advanced by the Song Renaissance teachings of Zhu Xi, the demand from Rome that anyone wishing to become a Christian must renounce Confucianism was tantamount to demanding that they renounce all government institutions in the country—an 18th-Century version of today’s subversive “color revolutions.”

For several decades, both the Chinese Emperor Kang Xi (1654-1722) and his Jesuit collaborators tried to convey the truth about Confucianism to Rome, but eventually the Venetian imperialists won out, forcing the Chinese to expel the missionaries altogether. Cooperation between East and West was broken in the early 18th Century, setting the stage for the arrival of the British imperial gunships.

Source: Executive Intelligence Review

- 275 reads

Human Rights

Fostering a More Humane World: The 28th Eurasian Economic Summi

Conscience, Hope, and Action: Keys to Global Peace and Sustainability

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020