NASA's TESS, Spitzer Missions Discover a World Orbiting a Unique Young Star

The newly discovered planet's parent star is still encircled by the disk of material from which both objects formed, giving scientists a glimpse at early planet evolution.

For more than a decade, astronomers have searched for planets orbiting AU Microscopii, a nearby star still surrounded by a disk of debris left over from its formation. Now scientists using data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and retired Spitzer Space Telescope report the discovery of a planet about as large as Neptune that circles the young star in just over a week.

This animated gif is an artist's concept of the planet AU Mic b and its young parent star. The faint band of light encircling the pair is a disk of gas and dust from which both the star and the planet formed.

The system, known as AU Mic for short, provides a one-of-kind laboratory for studying how planets and their atmospheres form, evolve and interact with their stars.

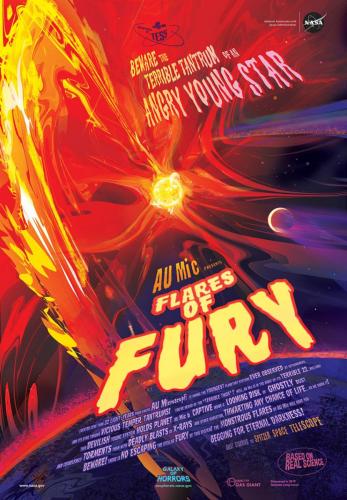

his rendering of the young planet AU Mic b is part of NASA's fun-but-informative Galaxy of Horrors poster series. The planet's star, AU Microscopii, emits powerful, fiery flares that would likely terrorize any lifeforms that tried to make a home here.

"AU Mic is a young, nearby M dwarf star. It's surrounded by a vast debris disk in which moving clumps of dust have been tracked, and now, thanks to TESS and Spitzer, it has a planet with a direct size measurement," said Bryson Cale, a doctoral student at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. "There is no other known system that checks all of these important boxes."

This animated artist's concept shows the dusty disk surrounding the star AU MIcroscopii. Astronomers have studied this system extensively but only recently identified the presence of a planet there. The find provides a laboratory for studying planet evolution and formation.

The new planet, AU Mic b, is described in a paper coauthored by Cale and led by his advisor Peter Plavchan, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at George Mason. Their report was published on Wednesday, June 24, in the journal Nature.

AU Mic b is featured in a new NASA poster available in English and Spanish, part of a Galaxy of Horrors series. The fun but informative series resulted from a collaboration of scientists and artists and was produced by NASA's Exoplanet Exploration Program Office.

AU Mic is a cool red dwarf star with an age estimated at 20 million to 30 million years, making it a stellar infant compared to our Sun, which is at least 150 times older. The star is so young that it primarily shines from the heat generated as its own gravity pulls it inward and compresses it. Less than 10% of the star's energy comes from the fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core, the process that powers stars like our Sun.

The system is located 31.9 light-years away in the southern constellation Microscopium. It's part of a nearby collection of stars called the Beta Pictoris Moving Group, which takes its name from a bigger, hotter A-type star that harbors two planets and is likewise surrounded by a debris disk.

Although the systems have the same age, their planets are markedly different. The planet AU Mic b almost hugs its star, completing an orbit every 8.5 days. It weighs less than 58 times Earth's mass, placing it in the category of Neptune-like worlds. Beta Pictoris b and c, however, are both at least 50 times more massive than AU Mic b and take 21 and 3.3 years, respectively, to orbit their star.

"We think AU Mic b formed far from the star and migrated inward to its current orbit, something that can happen as planets interact gravitationally with a gas disk or with other planets," said coauthor Thomas Barclay, an associate research scientist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and an associate project scientist for TESS at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "By contrast, Beta Pictoris b's orbit doesn't appear to have migrated much at all. The differences between these similarly aged systems can tell us a lot about how planets form and migrate."

Detecting planets around stars like AU Mic poses a particular challenge. These stormy stars possess strong magnetic fields and can be covered with starspots - cooler, darker and highly magnetic regions akin to sunspots - that frequently erupt with powerful stellar flares. Both the spots and their flares contribute to the star's brightness changes.

In July and August 2018, when TESS was observing AU Mic, the star produced numerous flares, some of which were more powerful than the strongest flares ever recorded on the Sun. The team performed a detailed analysis to remove these effects from the TESS data.

When a planet crosses in front of its star from our perspective, an event called a transit, its passage causes a distinct dip in the star's brightness. TESS monitors large swaths of the sky, called sectors, for 27 days at a time. During this long stare, the mission's cameras regularly capture snapshots that allow scientists to track changes in stellar brightness.

Regular dips in a star's brightness signal the possibility of a transiting planet. Usually, it takes at least two observed transits to recognize a planet's presence.

"As luck would have it, the second of three TESS transits occurred when the spacecraft was near its closest point to Earth. At such times, TESS is not observing because it is busy downlinking all of the stored data," said coauthor Diana Dragomir, a research assistant professor at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. "To fill the gap, our team was granted observing time on Spitzer, which caught two additional transits in 2019 and enabled us to confirm the orbital period of AU Mic b."

Spitzer was a multipurpose infrared observatory operating from 2003 until its decommissioning on Jan. 30, 2020. The mission proved especially adept at detecting and studying exoplanets around cool stars. Spitzer returned the AU Mic observations during its final year.

Because the amount of light blocked by a transit depends on the planet's size and orbital distance, the TESS and Spitzer transits provide a direct measure of AU Mic b's size. Analysis of these measurements show that the planet is about 8% larger than Neptune.

Observations from instruments on ground-based telescopes provide upper limits for the planet's mass. As a planet orbits, its gravity tugs on its host star, which moves slightly in response. Sensitive instruments on large telescopes can detect the star's radial velocity, its motion to-and-fro along our line of sight. Combining observations from the W. M. Keck Observatory and NASA's InfraRed Telescope Facility in Hawaii and the European Southern Observatory in Chile, the team concluded that AU Mic b has a mass smaller than 58 Earths.

This discovery shows the power of TESS to provide new insights into well-studied stars like AU Mic, where more planets may be waiting to be found.

"There is an additional candidate transit event seen in the TESS data, and TESS will hopefully revisit AU Mic later this year in its extended mission," Plavchan said. "We are continuing to monitor the star with precise radial velocity measurements, so stay tuned."

For decades, AU Mic has intrigued astronomers as a possible home for planets thanks to its proximity, youth and bright debris disk. Now that TESS and Spitzer have found one there, the story comes full circle. AU Mic is a touchstone system, a nearby laboratory for understanding the formation and evolution of stars and planets that will be studied for decades to come.

TESS is a NASA Astrophysics Explorer mission led and operated by MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. Additional partners include Northrop Grumman, based in Falls Church, Virginia; NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley; the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts; MIT's Lincoln Laboratory; and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. More than a dozen universities, research institutes and observatories worldwide are participants in the mission.

Source: Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- 288 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020