ESO Telescope Sees Signs of Planet Birth

The Twist Marks the Spot

Observations made with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) have revealed the telltale signs of a star system being born. Around the young star AB Aurigae lies a dense disc of dust and gas in which astronomers have spotted a prominent spiral structure with a ‘twist’ that marks the site where a planet may be forming. The observed feature could be the first direct evidence of a baby planet coming into existence.

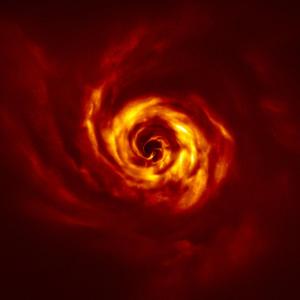

SPHERE image of the disc around AB Aurigae.

“Thousands of exoplanets have been identified so far, but little is known about how they form,” says Anthony Boccaletti who led the study from the Observatoire de Paris, PSL University, France. Astronomers know planets are born in dusty discs surrounding young stars, like AB Aurigae, as cold gas and dust clump together. The new observations with ESO’s VLT, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, provide crucial clues to help scientists better understand this process.

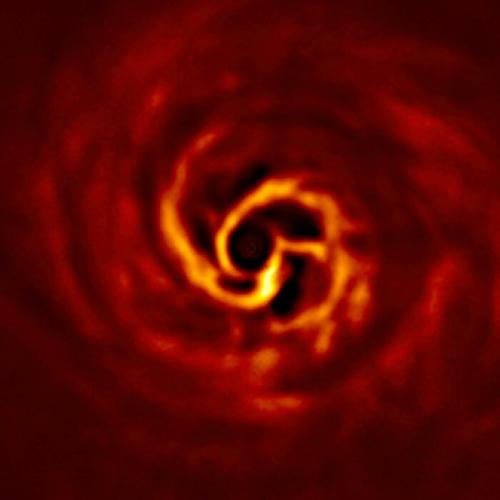

SPHERE image of the inner disc around AB Aurigae.

“We need to observe very young systems to really capture the moment when planets form,” says Boccaletti. But until now astronomers had been unable to take sufficiently sharp and deep images of these young discs to find the ‘twist’ that marks the spot where a baby planet may be coming to existence.

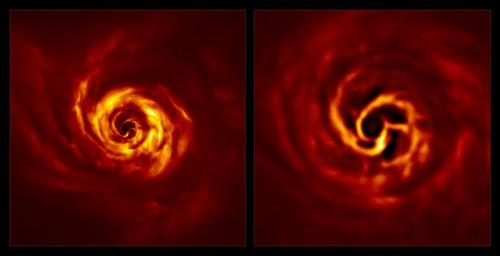

SPHERE images of the AB Aurigae system (side by side, annotated).

The new images feature a stunning spiral of dust and gas around AB Aurigae, located 520 light-years away from Earth in the constellation of Auriga (The Charioteer). Spirals of this type signal the presence of baby planets, which ‘kick’ the gas, creating “disturbances in the disc in the form of a wave, somewhat like the wake of a boat on a lake,” explains Emmanuel Di Folco of the Astrophysics Laboratory of Bordeaux (LAB), France, who also participated in the study. As the planet rotates around the central star, this wave gets shaped into a spiral arm. The very bright yellow ‘twist’ region close to the centre of the new AB Aurigae image, which lies at about the same distance from the star as Neptune from the Sun, is one of these disturbance sites where the team believe a planet is being made.

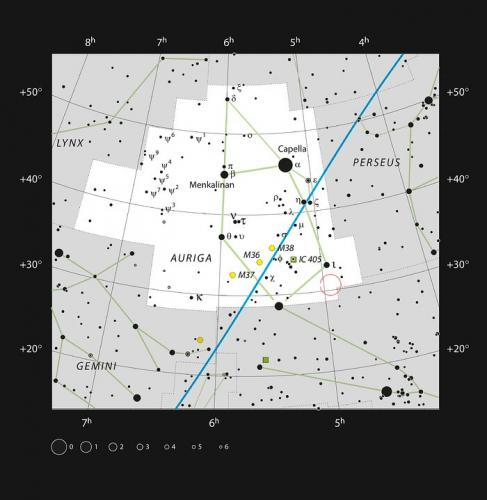

Wide-field view of the region of the sky where AB Aurigae is located.

Observations of the AB Aurigae system made a few years ago with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which ESO is a partner, provided the first hints of ongoing planet formation around the star. In the ALMA images, scientists spotted two spiral arms of gas close to the star, lying within the disc’s inner region. Then, in 2019 and early 2020, Boccaletti and a team of astronomers from France, Taiwan, the US and Belgium set out to capture a clearer picture by turning the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s VLT in Chile toward the star. The SPHERE images are the deepest images of the AB Aurigae system obtained to date.

Location of AB Aurigae in the constellation of Auriga.

With SPHERE's powerful imaging system, astronomers could see the fainter light from small dust grains and emissions coming from the inner disc. They confirmed the presence of the spiral arms first detected by ALMA and also spotted another remarkable feature, a ‘twist’, that points to the presence of ongoing planet formation in the disc. "The twist is expected from some theoretical models of planet formation,” says co-author Anne Dutrey, also at LAB. “It corresponds to the connection of two spirals — one winding inwards of the planet’s orbit, the other expanding outwards — which join at the planet location. They allow gas and dust from the disc to accrete onto the forming planet and make it grow."

ESO is constructing the 39-metre Extremely Large Telescope, which will draw on the cutting-edge work of ALMA and SPHERE to study extrasolar worlds. As Boccaletti explains, this powerful telescope will allow astronomers to get even more detailed views of planets in the making. “We should be able to see directly and more precisely how the dynamics of the gas contributes to the formation of planets,” he concludes.

Source: European Southern Observatory (ESO)

- 265 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020