Magnetic north and the elongating blob

For some years now, scientists have been puzzling over why the north magnetic pole has been making a dash towards Siberia. Thanks, in part, to ESA’s Swarm satellite mission, scientists are now more confident in the theory that tussling magnetic blobs deep below Earth’s surface are at the root of this phenomenon.

Unlike our geographic north pole, which is in a fixed location, magnetic north wanders. This has been known since it was first measured in 1831, and subsequently mapped drifting slowly from the Canadian Arctic towards Siberia.

Swirling iron.

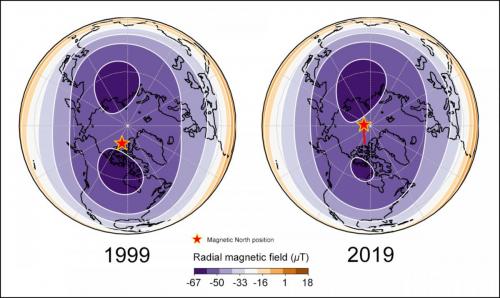

However, since the 1990s, this drift has turned into more of a sprint – going from its historic wandering of 0–15 km a year to its present speed of 50–60 km a year. This shift in pace has meant that the World Magnetic Model has had to be updated more frequently, which is vital for navigation on smart phones, for example.

The force that protects our planet.

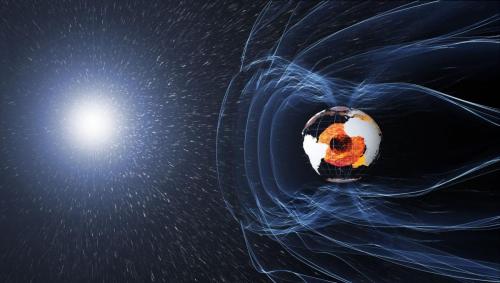

Our magnetic field exists because of an ocean of superheated, swirling liquid iron that makes up the outer core. Like a spinning conductor in a bicycle dynamo, this moving iron creates electrical currents, which in turn generate our continuously changing magnetic field.

Tug between magnetic blobs.

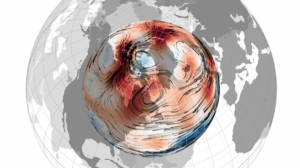

Numerical models based on measurements from space, including from ESA’s Swarm mission, have allowed scientists to construct global maps of the magnetic field. Tracking changes in the magnetic field can tell researchers how the iron in the core moves.

During ESA’s Living Planet Symposium last year, scientists from the University of Leeds in the UK reported that these satellite data showed that the position of the north magnetic pole is determined largely by a balance, or tug-of-war, between two large lobes of negative flux at the boundary between Earth’s core and mantle under Canada.

Following on from this, the research team has recently published their latest findings in Nature Geoscience.

Phil Livermore, from the University of Leeds, said, “By analysing magnetic field maps and how they change over time, we can now pinpoint that a change in the circulation pattern of flow underneath Canada has caused a patch of magnetic field at the edge of the core, deep within the Earth, to be stretched out. This has weakened the Canadian patch and resulted in the pole shifting towards Siberia.”

The big question is whether the pole will ever return to Canada or continue heading south.

“Models of the magnetic field inside the core suggest that, at least for the next few decades, the pole will continue to drift towards Siberia,” explained Dr Livermore.

“However, given that the pole’s position is governed by this delicate balance between the Canadian and Siberian patch, it would take only a small adjustment of the field within the core to send the pole back to Canada.”

Source: European Space Agency

- 249 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020