Cosmic Magnifying Glasses Find Dark Matter in Small Clumps

The mysterious material makes up most of the mass in the universe, yet scientists don't understand its fundamental properties. Hubble observations have provided new clues.

Using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and a new observing technique, astronomers have found that dark matter forms much smaller clumps than previously known. This result confirms one of the fundamental predictions of the widely accepted "cold dark matter" theory.

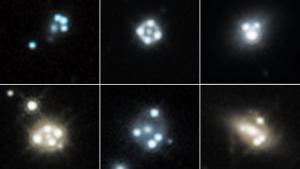

Each snapshot shows four distorted images of a background quasar (an extremely bright region in the center of some distant galaxies), surrounding the core of a massive foreground galaxy. The gravity of the foreground galaxy magnifies the quasar, an effect called gravitational lensing.

All galaxies, according to this theory, form and are embedded within clouds of dark matter. Dark matter itself consists of slow-moving, or "cold," particles that come together to form structures ranging from hundreds of thousands of times the mass of the Milky Way galaxy to clumps no more massive than the heft of a commercial airplane. (In this context, "cold" refers to the particles' speed.)

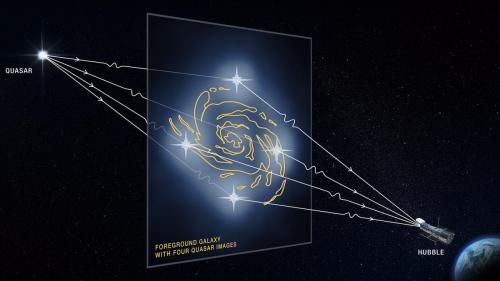

This graphic illustrates how a faraway quasar (an extremely bright region in the center of some distant galaxies) is altered by a massive foreground galaxy. The galaxy's powerful gravity warps and magnifies the quasar's light, producing four distorted images of the quasar.

The Hubble observation yields new insights into the nature of dark matter and how it behaves. "We made a very compelling observational test for the cold dark matter model and it passes with flying colors," said Tommaso Treu of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), a member of the observing team.

Dark matter is an invisible form of matter that makes up the bulk of the universe's mass and creates the scaffolding upon which galaxies are built. Although astronomers cannot see dark matter, they can detect its presence indirectly by measuring how its gravity affects stars and galaxies. Detecting the smallest dark matter formations by looking for embedded stars can be difficult or impossible because they contain very few stars.

While dark matter concentrations have been detected around large- and medium-sized galaxies, much smaller clumps of dark matter have not been found until now. In the absence of observational evidence for such small-scale clumps, some researchers have developed alternative theories, including "warm dark matter." This idea suggests that dark matter particles are fast moving, zipping along too quickly to merge and form smaller concentrations. The new observations do not support this scenario, finding that dark matter is "colder" than it would have to be in the warm dark matter alternative theory.

"Dark matter is colder than we knew at smaller scales," said Anna Nierenberg of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, leader of the Hubble survey. "Astronomers have carried out other observational tests of dark matter theories before, but ours provides the strongest evidence yet for the presence of small clumps of cold dark matter. By combining the latest theoretical predictions, statistical tools and new Hubble observations, we now have a much more robust result than was previously possible."

Hunting for dark matter concentrations devoid of stars has proved challenging. The Hubble research team, however, used a technique in which they did not need to look for the gravitational influence of stars as tracers of dark matter. The team targeted eight powerful and distant cosmic "streetlights," called quasars (regions around active black holes that emit enormous amounts of light). The astronomers measured how the light emitted by oxygen and neon gas orbiting each of the quasars' black holes is warped by the gravity of a massive foreground galaxy, which acts as a magnifying lens.

Using this method, the team uncovered dark matter clumps along the telescope's line of sight to the quasars, as well as in and around the intervening lensing galaxies. The dark matter concentrations detected by Hubble are 1/10,000th to 1/100,000th times the mass of the Milky Way's dark matter halo. Many of these tiny groupings most likely do not contain even small galaxies, and therefore would have been impossible to detect by the traditional method of looking for embedded stars.

The eight quasars and galaxies were aligned so precisely that the warping effect, called gravitational lensing, produced four distorted images of each quasar. The effect is like looking at a funhouse mirror. Such quadruple images of quasars are rare because of the nearly exact alignment needed between the foreground galaxy and background quasar. However, the researchers needed the multiple images to conduct a more detailed analysis.

The presence of the dark matter clumps alters the apparent brightness and position of each distorted quasar image. Astronomers compared these measurements with predictions of how the quasar images would look without the influence of the dark matter. The researchers used the measurements to calculate the masses of the tiny dark matter concentrations. To analyze the data, the researchers also developed elaborate computing programs and intensive reconstruction techniques.

"Imagine that each one of these eight galaxies is a giant magnifying glass," explained team member Daniel Gilman of UCLA. "Small dark matter clumps act as small cracks on the magnifying glass, altering the brightness and position of the four quasar images compared to what you would expect to see if the glass were smooth."

The researchers used Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 to capture the near-infrared light from each quasar and disperse it into its component colors for study with spectroscopy. Unique emissions from the background quasars are best seen in infrared light. "Hubble's observations from space allow us to make these measurements in galaxy systems that would not be accessible with the lower resolution of ground-based telescopes - and Earth's atmosphere is opaque to the infrared light we needed to observe," explained team member Simon Birrer of UCLA.

Treu added: "It's incredible that after nearly 30 years of operation, Hubble is enabling cutting-edge views into fundamental physics and the nature of the universe that we didn't even dream of when the telescope was launched."

The gravitational lenses were discovered by sifting through ground-based surveys such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and Dark Energy Survey, which provide the most detailed three-dimensional maps of the universe ever made. The quasars are located roughly 10 billion light-years from Earth; the foreground galaxies, about 2 billion light-years.

The number of small structures detected in the study offers more clues about dark matter's nature. "The particle properties of dark matter affect how many clumps form," Nierenberg explained. "That means you can learn about the particle physics of dark matter by counting the number of small clumps."

However, the type of particle that makes up dark matter is still a mystery. "At present, there's no direct evidence in the lab that dark matter particles exist," Birrer said. "Particle physicists would not even talk about dark matter if the cosmologists didn't say it's there, based on observations of its effects. When we cosmologists talk about dark matter, we're asking 'how does it govern the appearance of the universe, and on what scales?'"

Astronomers will be able to conduct follow-up studies of dark matter using future NASA space telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope and the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), both infrared observatories. Webb will be capable of efficiently obtaining these measurements for all known quadruply lensed quasars. WFIRST's sharpness and large field of view will help astronomers make observations of the entire region of space affected by the immense gravitational field of massive galaxies and galaxy clusters. This will help researchers uncover many more of these rare systems.

Source: Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- 257 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020