Ozone hole set to close

The size of the ozone hole fluctuates – usually forming each year in August, with its peak in October, before finally closing in late November or December. Not only will the hole close earlier than usual in 2019, but it is also the smallest it has been in 30 years owing to unusual atmospheric conditions.

Forecasts from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), which uses total ozone measurements from the Copernicus Sentinel-5P mission processed at the German Aerospace Center, have forecasted that this year’s ozone hole will close sooner than usual.

Ozone_hole_set_to_close_pillars

Antje Inness, CAMS Senior Scientist commented, “The ozone hole’s maximum extent this year was around 10 million sq km, less than half of the size the ozone hole usually reached in the last decades. This makes it one of the smallest ozone holes since the 1980s. Our CAMS ozone forecasts predict that the ozone hole will close within a week.”

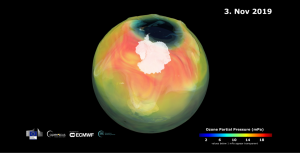

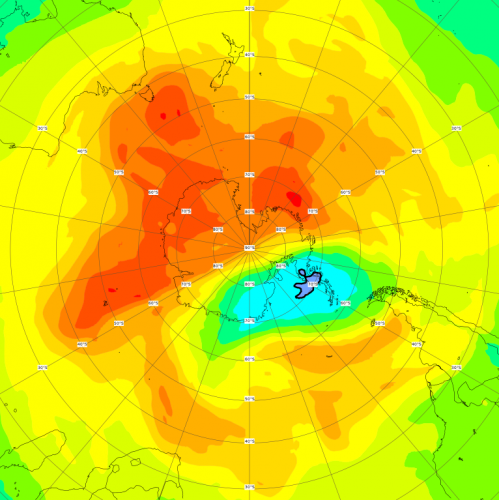

Ozone forecast charts.

ESA’s mission manager for Copernicus Sentinel-5P, Claus Zehner, noted, “This record-breaking small ozone hole size and duration during 2019 was caused by a warming of the stratosphere over the South Pole. However, it’s important to note that this is an unusual event and does not indicate that the global ozone recovery is speeding up.”

The animation shows the size of the ozone hole in 2019 compared to 2018, based on Copernicus Sentinel-5P measurements.

Large fluctuations in polar vortices and temperatures in the stratosphere lead to ozone holes that vary in size. This year, the warmer polar stratosphere caused a slowing down of the wind fields around the South Pole, or the polar vortex, and reduced the formation of the ‘polar stratospheric clouds’ that enable the chemistry that leads to rapid ozone loss.

Ozone hole duration and extension as monitored by CAMS

Josef Aschbacher, ESA’s Director of Earth Observation programmes, said, "The ozone hole is a perfect example where scientific evidence led to significant policy change and subsequently changes in human behaviour. The ozone hole was discovered in the 1970s, continuously monitored from space and by in situ devices and, finally in the 1980s led to the Montreal Protocol forbidding the use of chlorofluorocarbons.

"Today, the ozone hole is recovering thanks to clear political action. This example shall serve as inspiration for climate change."

High up in the stratosphere, the ozone acts as a shield to protect us from the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation, which is associated with skin cancer and cataracts, as well as other environmental issues.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the widespread use of damaging chlorofluorocarbons in products such as refrigerators and aerosol tins damaged ozone high up in our atmosphere – which led to a hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica.

In response to this, the Montreal Protocol was created in 1987 to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production and consumption of these harmful substances, which is leading to a recovery of the ozone layer.

Recovery of the ozone hole will continue over the coming years. In the 2018 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion, data shows that the ozone layer in parts of the stratosphere has recovered at a rate of 1-3% per decade since 2000. At these projected rates, the Northern Hemisphere and mid-latitude ozone is predicted to recover by around 2030, followed by the Southern Hemisphere around 2050, and polar regions by 2060.

ESA has been involved in monitoring ozone for many years. Launched in October 2017, Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite maps a multitude of air pollutants around the globe. With its state-of-the-art instrument, Tropomi, it is able to detect atmospheric gases to image air pollutants more accurately and at a higher spatial resolution than ever before from space.

Source: European Space Agency

- 253 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020