Hubble Pushed Beyond Limits to Spot Clumps of New Stars in Distant Galaxy

When the universe was young, stars formed at a much higher rate than they do today. By peering across billions of light-years of space, Hubble can study this early era. But at such distances, galaxies shrink to smudges that hide key details. Astronomers have teased out those details in one distant galaxy by combining Hubble’s sharp vision with the natural magnifying power of a gravitational lens. The result is an image 10 times better than what Hubble could achieve on its own, showing dense clusters of brilliant, young stars that resemble cosmic fireworks.

When it comes to the distant universe, even the keen vision of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope can only go so far. Teasing out finer details requires clever thinking and a little help from a cosmic alignment with a gravitational lens.

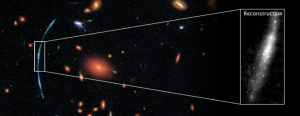

By applying a new computational analysis to a galaxy magnified by a gravitational lens, astronomers have obtained images 10 times sharper than what Hubble could achieve on its own. The results show an edge-on disk galaxy studded with brilliant patches of newly formed stars.

“When we saw the reconstructed image we said, ‘Wow, it looks like fireworks are going off everywhere,’” said astronomer Jane Rigby of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The galaxy in question is so far away that we see it as it appeared 11 billion years ago, only 2.7 billion years after the big bang. It is one of more than 70 strongly lensed galaxies studied by the Hubble Space Telescope, following up targets selected by the Sloan Giant Arcs Survey, which discovered hundreds of strongly lensed galaxies by searching Sloan Digital Sky Survey imaging data covering one-fourth of the sky.

The gravity of a giant cluster of galaxies between the target galaxy and Earth distorts the more distant galaxy’s light, stretching it into an arc and also magnifying it almost 30 times. The team had to develop special computer code to remove the distortions caused by the gravitational lens, and reveal the disk galaxy as it would normally appear.

The resulting reconstructed image revealed two dozen clumps of newborn stars, each spanning about 200 to 300 light-years. This contradicted theories suggesting that star-forming regions in the distant, early universe were much larger, 3,000 light-years or more in size.

“There are star-forming knots as far down in size as we can see,” said doctoral student Traci Johnson of the University of Michigan, lead author of two of the three papers describing the research.

Without the magnification boost of the gravitational lens, Johnson added, the disk galaxy would appear perfectly smooth and unremarkable to Hubble. This would give astronomers a very different picture of where stars are forming.

While Hubble highlighted new stars within the lensed galaxy, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will uncover older, redder stars that formed even earlier in the galaxy’s history. It will also peer through any obscuring dust within the galaxy.

“With the Webb Telescope, we’ll be able to tell you what happened in this galaxy in the past, and what we missed with Hubble because of dust,” said Rigby.

Source: Hubblesite

- 424 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020