Background suppression for super-resolution light microscopy: KIT-developed STEDD nanoscopy yields enhanced image quality for analyzing three-dimensional molecules and cell structures -- presentation in Nature Photonics

Optical microscopy is applied widely in the life sciences sector. Among others, it is used to minimally invasively examine living cells. Resolution of conventional light microscopy, however, is limited to half the wavelength of light, i.e. about 200 nm, such that finest cellular structures are blurred in the image. In the past years, various nanoscopy methods were developed which overcome the diffraction limit and produce images of highest resolution. Stefan W. Hell, Eric Betzig, and William Moerner were granted the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their nanoscopy methods in 2014. Now, researchers of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) have refined the STED (Simulated Emission Depletion) nanoscopy method developed by Hell by modifying image acquisition in a way that background is suppressed efficiently. The resulting enhanced image quality is particularly advantageous for quantitative data analysis of three-dimensional, densely arranged molecules and cell structures. The new nanoscopy method named STEDD (Stimulated Emission Double Depletion) developed by the team of Professor Gerd Ulrich Nienhaus of KIT's Institute of Applied Physics (APH) and Institute of Nanotechnology (INT) is presented in Nature Photonics.

In fluorescence microscopy, the sample to be studied is scanned with a strongly focused light beam to make dye molecules emit fluorescence light. The light quanta are registered pixel by pixel to build up the image. In STED nanoscopy, the excitation beam used for scanning is overlapped by another beam, the so-called STED beam. Its light intensity is located around the excitation beam. In the center, it is zero. Moreover, the STED beam is shifted towards higher wavelengths. The STED beam uses the physical effect that was first described by Albert Einstein 100 years ago, namely, stimulated emission, to switch off fluorescent excitation everywhere, except in the center where the STED beam has zero intensity. In this way, excitation is confined and a sharper light spot results for scanning. The highly resolved STED image, however, always has a background of low resolution, which is due to incomplete stimulated depletion and fluorescence excitation by the STED beam itself.

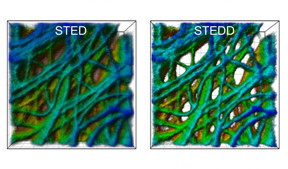

A cancer cell under the microscope: The STED image (left) has a background of low resolution. In the STEDD image (right), background suppression results in much better visible structures. CREDIT Image: APH/KIT

The team of Gerd Ulrich Nienhaus has now extended this STED method by another STED beam. The STED2 beam follows the STED beam with a certain time delay and eliminates the useful signal in the center, such that only background excitation remains. "The STED method is based on recording two images," Professor Nienhaus explains. "Photons registered prior to and after the arrival of the STED2 beam contribute to the first and second image, respectively." The second image containing background only is subtracted pixel by pixel, with a specific weight factor, from the first image that contains the useful signal plus background. The result is a background-free image of highest resolution.

source: Nanotechnology Now

- 314 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020