TCGA study identifies genomic features of cervical cancer

Investigators with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network have identified novel genomic and molecular characteristics of cervical cancer that will aid in the subclassification of the disease and may help target therapies that are most appropriate for each patient. The new study, a comprehensive analysis of the genomes of 178 primary cervical cancers, found that over 70 percent of the tumors had genomic alterations in either one or both of two important cell signaling pathways. The researchers also found, unexpectedly, that a subset of tumors did not show evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The study included authors from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), both parts of the National Institutes of Health.

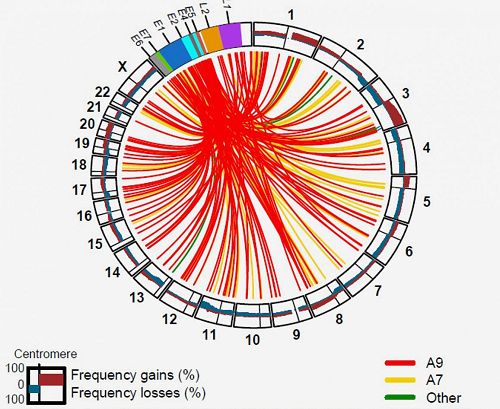

Circos plot showing cervical cancer chromosomes affected by HPV oncogenes.

Cervical cancer accounts for more than 500,000 new cases of cancer and more than 250,000 deaths each year worldwide. “The vast majority of cases of cervical cancer are caused by persistent infection with oncogenic types of HPV. Effective preventive vaccines against the most oncogenic forms of HPV have been available for a number of years, with vaccination having the long-term potential to reduce the number of cases of cervical cancer,” said NCI Acting Director Douglas Lowy, M.D.

“However, most women who will develop cervical cancer in the next couple of decades are already beyond the recommended age for vaccination and will not be protected by the vaccine,” noted Dr. Lowy. “Therefore, cervical cancer is still a disease in need of effective therapies, and this latest TCGA analysis could help advance efforts to find drugs that target important elements of cervical cancer genomes in addition to the HPV genes.”

An aspect of the study that is of particular interest was the identification of a unique set of eight cervical cancers that showed molecular similarities to endometrial cancers. These endometrial-like cancers were mainly HPV-negative, and they all had high frequencies of mutations in the KRAS, ARID1A, and PTEN genes.

“The identification of HPV-negative endometrial-like tumors confirms that not all cervical cancers are related to HPV infection and that a small percentage of cervical tumors may be due to strictly genetic or other factors,” noted Jean-Claude Zenklusen, Ph.D., director of NCI’s TCGA program office. “This aspect of the research is one of the most intriguing findings to come out of the TCGA program, which has been looking at more than 30 tumor types over the past decade.”

Because immunotherapies are becoming increasingly important for cancer therapy, the investigators examined genes that code for known immune targets to see if any were amplified, which may predict responsiveness to immunotherapy. They found amplification of several such genes, specifically CD274 (which encodes the PD-L1 immune checkpoint protein) and PDCD1LG2 (which encodes the PD-L2 immune checkpoint protein). Several checkpoint inhibitors have been shown to be effective immunotherapeutic agents. In addition, the TCGA analysis identified several novel mutated genes in cervical cancer, including MED1, ERBB3, CASP8, HLA-A, and TGFBR2. The researchers also identified several cases with gene fusions involving the gene BCAR4, which produces a long noncoding RNA that has been shown to induce responsiveness to lapatinib, an oral drug that inhibits a key pathway in breast cancer. Therefore, BCAR4 may be a potential therapeutic target for cervical cancers with this alteration.

When analyzing the biology behind the molecular alterations in these tumors, the researchers found that nearly three-quarters of cervical cancers had genomic alterations in either one or both of the PI3K/MAPK and TGF-beta signaling pathways, which may also provide targets for therapy. The authors noted that an important question raised by this study is whether HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors will respond differently to targeted therapies.

Source: U.S. National Institutes of Health

- 386 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020