Rising employment overshadowed by unprecedented wage stagnation

Economic growth is picking up and unemployment has reached record lows in some OECD countries but wages continue to stagnate. Unless countries can break this cycle, public belief in the recovery will be undermined and labour market inequality will widen, according to a new OECD report.

The OECD Employment Outlook 2018 says that the employment rate for people aged 15-74 in the OECD area reached 61.7% in the OECD area at the end of 2017. For the first time, there are more people with a job today than before the crisis. The employment rate in the OECD is expected to reach 62.1% by the end of this year and 62.5% in the fourth quarter of 2019. Some of the strongest improvements occurred among disadvantaged groups, such as older workers, mothers with young children, youth and immigrants.

Unemployment rates are below, or close to, pre-crisis levels in most countries. Job vacancies have also reached record highs in Japan, the euro area, the United States and Australia. The OECD unemployment rate is predicted to continue falling, to reach 5.3% at the end of 2018 and 5.1% the following year. Yet the picture continues to be mixed in terms of jobs quality and security, while poverty has grown among the working age population, reaching 10.6% in 2015 compared to 9.6% a decade earlier.

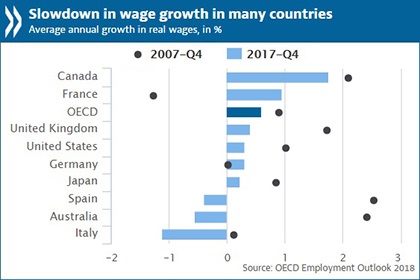

Wage growth remains remarkably more sluggish than before the financial crisis. At the end of 2017, nominal wage growth in the OECD area was only half of what it was ten years earlier: in Q2 2007, when the average of unemployment rates of OECD countries was about the same as now, the average nominal wage growth was 5.8% vs 3.2% in Q4 2017.

More worryingly, wage stagnation affects low-paid workers much more than those at the top: real labour incomes of the top 1% of earners have increased much faster than those of median full-time workers in recent years, reinforcing a long-standing trend.

“This trend of wageless growth in the face of a rise in employment highlights the structural changes in our economies that the global crisis has deepened, and it underlines the urgent need for countries to help workers, especially the low-skilled,” said OECD Secretary-General Ángel Gurría, launching the report in Paris. “Well-targeted policy measures and closer collaboration with social partners are needed to help workers adapt to and benefit from a rapidly evolving world of work, in order to achieve inclusive growth.”

Low inflation and the major productivity slowdown have contributed to wage stagnation, as well as a rise in low-paying jobs. The Outlook notes a significant worsening in the average earnings for part-time workers relative to full-time workers. Declining coverage of unemployment benefits in many countries and persisting long-term unemployment may also have contributed. Fewer than one-in-three jobseekers receive unemployment benefits on average across the OECD, and the longer-term downward trend of benefit coverage has continued in many countries since the crisis.

Countries should develop high-quality education and training systems that provide learning opportunities throughout the life course, says the OECD. Evidence suggests that the low skilled are three times less likely to receive training than high-skilled workers. More needs to be done to overcome this gap, as highlighted in the recently launched Policy Framework for Inclusive Growth, with better targeted training measures for workers at risk of becoming trapped in low-wage, low-quality jobs or in joblessness, together with a greater involvement of employers, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises that struggle to offer training.

New evidence in the Outlook shows that co-ordinated collective bargaining systems, with strong and self-regulated social partners and effective mediation bodies, contribute to high levels of employment, a better quality work environment, including more training opportunities, and greater resilience of the labour market to shocks.

This year’s Outlook includes analysis of how labour market gender inequalities evolve over the career of men and women. Even if the gap in annual average labour income between men and women has fallen significantly, women's annual labour income was still 39% lower on average than that of men in 2015 across the OECD. This measure takes account of gender differences in participation, as well as of hours worked and hourly earnings when employed.

Much of this gap is generated in the first half of women’s careers, the report finds. Family policies, measures to encourage behavioural changes and actions promoting changes in the workplace, such as increased take-up of flexible working time arrangements by both fathers and mothers, would help create more inclusive career paths for both men and women.

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- 240 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020