Development aid stable in 2017 with more sent to poorest countries

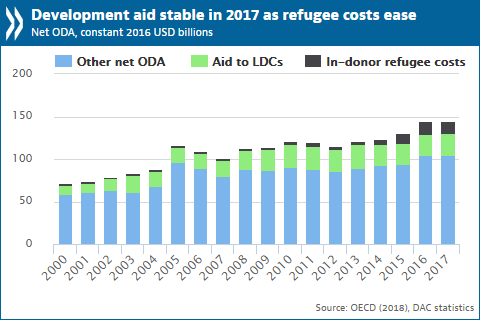

Foreign aid from official donors totalled USD 146.6 billion in 2017, a small decrease of 0.6% from 2016 in real terms as less money was spent on refugees inside donor countries but with more funds flowing to countries most in need of aid, according to preliminary official data collected by the OECD.

Stripping out in-donor refugee costs, net ODA was up 1.1% from 2016 in real terms (i.e. correcting for inflation and currency fluctuations). ODA spent by donor countries on hosting refugees fell by 13.6% to USD 14.2 billion as refugee arrivals, mainly in Europe, decreased. In-donor refugee costs were 9.7% of total net ODA, down from 11% in 2016.

Bilateral (country to country) aid to least-developed countries increased by 4% in real terms to USD 26 billion, following several years of declines. Aid to Africa rose by 3% to USD 29 billion and, within that, aid to sub-Saharan Africa was also up 3% to USD 25 billion. Humanitarian aid rose by 6.1% in real terms to USD 15.5 billion.

The dip in the headline figure left total ODA from members of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) equivalent to just 0.31% of their combined gross national income, down from 0.32% in 2016 and well below a United Nations target to keep ODA at or above 0.7% of donor GNI.

“It is good to see more money going where it is most needed, but it is still not enough. Too many donors are still far behind the 0.7% target,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría, presenting the figures. “Supporting developing countries with ODA is the fastest route to spreading stability and inclusive growth and it will be vital for developing countries to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Donor countries should be using this time of economic expansion to step up their efforts, both increasing their levels of foreign aid and ensuring it goes to the poorest countries.” Read full speech

A 1988 DAC rule allows donor countries to count certain refugee expenses as ODA for the first year after their arrival. Australia, Korea and Luxembourg did not count any in-donor refugee costs as ODA in 2017 but nine countries spent over 10% of their ODA on refugees. Among them, Germany, Greece, Iceland and Italy used over 20% of ODA for in-donor refugee costs.

Overall, total net ODA flows rose in 11 countries in 2016, with the biggest increases in France, Italy, Japan and Sweden. ODA fell in 18 countries, in many cases due to lower numbers of refugee arrivals, with the largest declines seen in Australia, Austria, Greece, Hungary, Norway, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland.

Of the several non-DAC members who report their aid flows to the OECD, the United Arab Emirates posted the highest ODA/GNI ratio in 2017 at 1.31% and Turkey the second-highest at 0.95%.

“I am encouraged to see a rise in ODA being spent in least-developed countries and I would like to call on DAC members to continue this effort. We should always be aiming to invest ODA for long-term purposes in countries most in need, and be cautious in using it for loans to middle-income countries,” said DAC Chair Charlotte Petri Gornitzka.

Five DAC members – Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom – met the United Nations target in 2017 for an ODA/GNI ratio of at least 0.7%. Having achieved the target in 2016, Germany slipped back in 2017 to join 24 other DAC donors under the threshold.

ODA makes up over two thirds of external finance for least-developed countries. The DAC is pushing for ODA to be better used as a lever to generate private investment and domestic tax revenue in poor countries to help achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Most ODA is in the form of grants, yet the volume of loans to developing countries rose 13% in 2017. For some donors concessional loans accounted for over a quarter of bilateral ODA.

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- 337 reads

Human Rights

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

The Peace Bell Resonates at the 27th Eurasian Economic Summit

Declaration of World Day of the Power of Hope Endorsed by People in 158 Nations

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020