Structural reforms more important than ever for a strong and balanced economic recovery

Structural reforms offer governments a powerful tool to boost economic growth, create jobs and bring about a strong and balanced economic recovery, according to the OECD’s latest Going for Growth report.

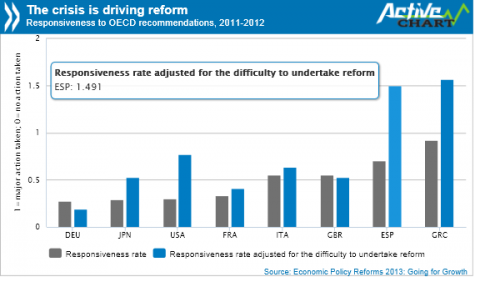

This year's report assesses and compares progress that countries have made on structural reforms since 2011 and takes a fresh look at reform priorities to revive growth sustainably and boost employment. It shows that the pace of reform has accelerated where it is most needed – in the European countries hardest hit by sovereign debt duress, including Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

The report draws attention to the more moderate pace of reform in other euro area countries, notably those with current account surpluses, like Germany or the Netherlands. The highest-income OECD countries, like Norway, Switzerland and the United States, and key emerging-market economies are also shown to have made more limited progress on key reforms.

Sructural reforms can boost long-term growth and welfare but also underpin confidence and take some of the pressure off monetary and fiscal policies to buttress the recovery," said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría. “The road to a strong recovery remains fraught with challenges but measures taken in Europe and the United States have reduced the likelihood of a worst-case scenario." Mr. Gurría said. “We have reached a point where bold and concerted action to get the right mix of macro and structural policies can make an upside scenario a real possibility.”

Mr. Gurría presented the report in Moscow with the Russian Federation’s finance minister Anton Siluanov, ahead of the 15-16 February meeting of G20 finance ministers. He said its key country-specific structural reform recommendations are applicable to OECD and G20 countries alike.

Since Going for Growth was launched in 2005, the annual report has identified key reform priorities to boost economic activity and raise living standards in each OECD country. Since 2011, the report also addresses reform potential in Brazil, India, Indonesia, China, the Russian Federation and South Africa - the so-called BRICS - and is the basis of the OECD’s wider contribution to the G20 Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth.

“The good news is that many countries have stepped up their efforts in recent years” Mr. Gurría said. “Active reforms in surplus and deficit countries alike would help achieve a quicker rebalancing of the global world economy, both globally and in the euro area.”

Dealing with the job market legacy of the crisis is a common challenge facing OECD and G20 countries, according to the report. Compared with previous editions, Going for Growth 2013 contains a marked increase in recommendations aimed at helping cash-strapped governments devise methods to maintain social benefits for the unemployed while improving labour market policies that will help get people back to work:

•In Europe, where unemployment is still above pre-crisis levels, many countries (including Denmark, France, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden) still need to lower barriers to job creation, hiring and mobility, while improving incentives to take up work.

•In Japan and Korea, raising the labour force participation of women is key, and will require better benefits systems and improved childcare policies.

•In lower-income OECD countries (like Chile, Mexico and Turkey) and the BRICS, reducing informality is a common challenge, so governments must improve incentives to create and take jobs in the formal sector.

•In the United States, unemployment has receded somewhat from its post-recession peak but the number of long-term unemployed and discouraged job seekers remain high, calling for programmes that provide training and employment services to be beefed up and streamlined.

One special feature of this year’s report is to explore the side effects of pro-growth policies on other objectives, such as reducing income inequalities and preserving the environment. Fostering greater equity in access to education - a priority for quite a number of countries, in advanced and emerging economies of the G20 alike - is a good case in point. But the report also finds that shifting part of the tax burden from labour to consumption is good for growth but likely to widen income inequalities. These policy trade-offs need to be borne in mind when designing growth policy packages.

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- 424 reads

Human Rights

Fostering a More Humane World: The 28th Eurasian Economic Summi

Conscience, Hope, and Action: Keys to Global Peace and Sustainability

Ringing FOWPAL’s Peace Bell for the World:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates’ Visions and Actions

Protecting the World’s Cultural Diversity for a Sustainable Future

Puppet Show I International Friendship Day 2020